Omer Asan: Greek-speaking writer from Turkey

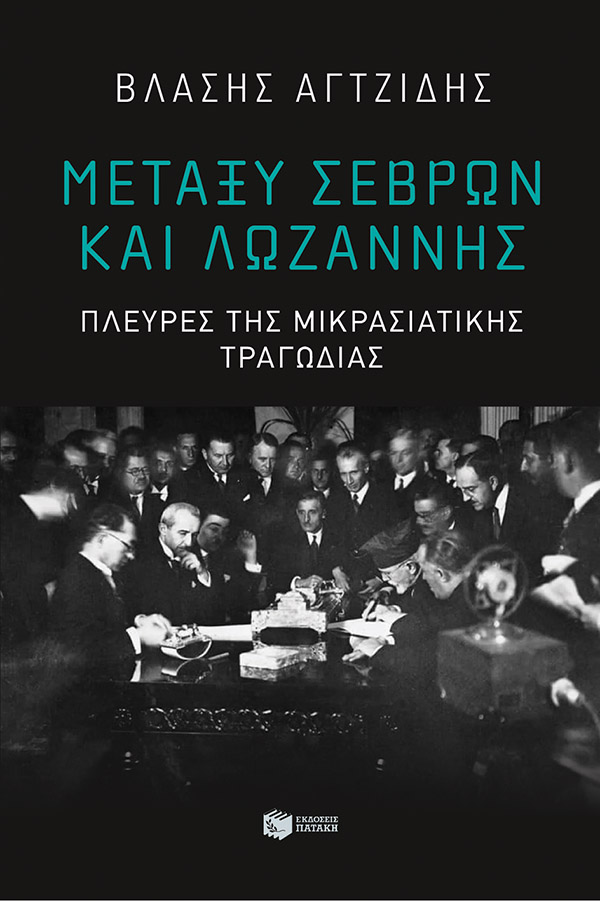

Πριν από αρκετά χρόνια, όταν είχε μεταφραστεί το βιβλίο του Omer Asan «Pontos Kulturu« στα ελληνικά με τίτλο: «Ο Πολιτισμός του Πόντου», είχα επιμεληθεί kαι προλογίσει μια πολύ ενδιαφέρουσα συνέντευξη του συγγραφέα, η οποία δημοσιεύτηκε στην «Kαθημερινή» στις 30 Iανουαρίου 2000 με τον τίτλο «Tουρκία: 300.000 ελληνόφωνοι ζητούν ταυτότητα».

H ίδια συνέντευξη με τον τίτλο «Omer Asan: Greek-speaking writer from Turkey and a guide to the Pontian culture», δημοσιεύτηκε λίγο αργότερα στο αγγλόφωνο ένθετο της «Kαθημερινής» στην εφημ. «Herald Tribune». Όταν ξεκίνησε η δικαστική περιπέτεια του Asan, δύο χρόνια αργότερα, η συγκεκριμένη συνέντευξη συμπεριλήφθηκε, στα «τεκμήρια ενοχής» που οδήγησαν στην παραπομπή του συγγραφέα με την κατηγορία της διαμελιστικής προπαγάνδας κατά του τουρκικού κράτους. Εκείνη την εποχή είχε τεθεί σε εφαρμογή η κατασταλτική πολιτική των τουρκικών αρχών κατά των ελληνοφώνων, κάτι που οδήγησε εκτός από τις διώξεις, σε εκφασισμό της περιοχής του Πόντου με την ανάπτυξη μαζικών οργανώσεων Γκρίζων Λύκων και προσπάθεια εκρίζωσης της ελληνοφωνίας.

H ίδια συνέντευξη με τον τίτλο «Omer Asan: Greek-speaking writer from Turkey and a guide to the Pontian culture», δημοσιεύτηκε λίγο αργότερα στο αγγλόφωνο ένθετο της «Kαθημερινής» στην εφημ. «Herald Tribune». Όταν ξεκίνησε η δικαστική περιπέτεια του Asan, δύο χρόνια αργότερα, η συγκεκριμένη συνέντευξη συμπεριλήφθηκε, στα «τεκμήρια ενοχής» που οδήγησαν στην παραπομπή του συγγραφέα με την κατηγορία της διαμελιστικής προπαγάνδας κατά του τουρκικού κράτους. Εκείνη την εποχή είχε τεθεί σε εφαρμογή η κατασταλτική πολιτική των τουρκικών αρχών κατά των ελληνοφώνων, κάτι που οδήγησε εκτός από τις διώξεις, σε εκφασισμό της περιοχής του Πόντου με την ανάπτυξη μαζικών οργανώσεων Γκρίζων Λύκων και προσπάθεια εκρίζωσης της ελληνοφωνίας.

Στην πολιτική αυτή συνέβαλαν ανόητοι της ελλαδικής πλευράς, είτε όταν αφελώς προσπαθούσαν να δημιουργήσουν (από την ελλαδική τους ασφάλεια) μειονοτικά ζητήματα στην Toυρκία εκμεταλλευόμενοι την ύπαρξη ελληνοφωνίας, είτε ως πράκτορες της ΚΥΠ επιχειρώντας να στρατολογήσουν κατασκόπους. Για το θλιβερό αυτό ζήτημα δείτε εδώ:

https://pontosandaristera.wordpress.com/2007/02/22/25-2-07/

Η περιπέτεια αυτή του Omer Asan έληξε δύο χρόνια αργότερα και το βιβλίο αφέθηκε ελεύθερο να κυκλοφορήσει και πάλι στην Τουρκία.

Newspaper : «International Herald Tribune», 25 April 2000

Omer Asan: Greek-speaking writer from Turkey and a guide to the Pontian culture

.

Pontos Kültürü or Pontos Culture is a 1996 book by Turkish author Ömer Asan about the Greek Muslims of Trabzon Province.

‘I began the search for my identity because the language my ancestors spoke was not Turkish’

«One of the most important books published in Greece last year was Omer Asan’s «The Civilization of the Pontos» (Kyriakidis Publishers, Thessaloniki). Now Greeks have the opportunity to read this book, first published as «Pontos Kulturu,» in 1996 in Istanbul, by Belge. A second edition is in press. Omer Asan, an economist, comes from Of, in Trebizond, northeastern Turkey, an area with a strong Islamic tradition and a substantial Greek-speaking population. In addition to the Of version of the Pontian dialect, Asan speaks Modern Greek fluently. The writer was involved in the Left and was prosecuted for it during the 1980s. His father, a member of the Turkish Communist Party, was imprisoned after the military coups of 1971 and 1981. Omer Asan belongs to the post-dictatorship generation. He came to Greece last year for the launching of the Greek edition of his book, and this interview was conducted during his visit.»

Vlassis Agtzidis

Are there Greek speakers in Turkey today who speak the Pontian dialect?

There are still people in Turkey today who speak and understand Pontian, which is the oldest surviving Greek dialect. The members of this community come from Trebizond and are scattered throughout Turkey, or have emigrated to other countries. Pontian is spoken in 60 villages in the Trebizond region, most of them in the Of area. At a conservative estimate, I would say this dialect is spoken by around 300,000 people.

You refer constantly to the «identity problem.» Why is this so important to you?

Nowadays the identity problem comes up more often, and this is because traditional explanations, like official identity cards, don’t give adequate answers. Some say the search for identity is a fashion that comes and goes. In their view, everyone is an individual, a human being and nothing else. Regardless of what anyone thinks, I consider the important thing is to protect our language, which we inherited from our forebears, and which is disappearing because we don’t care about its disappearance, and also to protect our culture and the identity it created for us. Throughout the history of mankind, many ethnic groups living in the same geographical area have been absorbed by the dominant culture. Personally I am against others today sharing the fate of ethnic cultural groups which, during the course of history, were sometimes incorporated into the dominant culture and sometimes assimilated by force.

You often refer to the question, «Who am I?» to define the motives for specific research. Did your personal search play a decisive part?

I began to search for my identity because of the fact that the language my ancestors spoke was not Turkish. Because in the village, in town, at school, they taught us that we were Turks. In the neighborhood, at school, at work, we spoke Turkish. But at home, in the village, my grandfather, my grandmother, everyone in the family spoke to each other in the language we called «Romaiika.» So what were we, «Romioi» or Turks? Now we speak Turkish. In my village the old people speak Romaiika, but they are the last to use the language. The coming generations will not be able to hear it and learn it. Let’s say that we have agreed, as far as the present is concerned: We speak Turkish, therefore we are Turkish. But who were we until now, what happened to make us become Turks? By asking «Who am I?» I plunged into the unknown. I had to find the answer to this question at any cost. And that is how this adventure began.

When did this adventure begin, and what was your research based on?At the end of the 1980s I began researching our identity and culture. But in Turkey I didn’t manage to find written sources, or anything related to the language we spoke. I began, in amateur fashion, to collect Pontian words. I asked all the old people I met about our identity and language. I spoke to Turkish experts and researchers and discovered to my surprise that no work had been done in this field. At that time, aiming to find out at least a little information, I wrote letters and sent them to addresses in Greece that I had learned of purely by chance. In 1993, just when I was about to give up hope, I was invited to a Pontian festival in Kallithea, Attica. What I saw and the sounds I heard there literally changed my life. I was astonished that hundreds of kilometers from the land where I was born, I heard songs in the language of my ancestors, accompanied by the lyra; that I danced with unknown people in another country, and that I could talk and make myself understood in Pontian, which I thought was a language that was no use at all.

So I decided to focus my research on Erenkioi, my village in Of, and to study its living culture as an extant trace of Pontian culture. The result was this book that was published first in Turkey and then in Greece. It is in six parts, including the theoretical context, historical and ethnographic details, popular literature, folklore, nomenclature, a glossary and bibliography.

How was your book received in Turkey? Were there any problems with publication?

The book had an extremely good reception in academic circles, since it filled a gap in modern Turkish learning. The second edition is already in press. But it did give rise to misunderstandings, both in Turkey and in Greece. Both sides interpreted the book differently. I didn’t come to Greece for three years, because of political incidents between the two countries. I hope that the improvement in the climate will facilitate scientific research into taboo subjects. And also that some groups in Greece that speak in the name of the Greek-speakers of Turkey will start to show more respect for that population.What are the greatest problems arising from the investigation of questions of identity and national culture?

In today’s world, problems centered on identity are not easily resolved. Indeed, when the question of ethnic identity arises, the alarm it causes can lead to conflict. The most recent example is the tragedy that occurred in Kosovo. Besides, we observe clashes – close by, in the heart of Europe – that stem from the aspirations of groups who share a common identity to create nations.

However, we must realize that at the end of this century, when cultural nationalism is being fomented and has become fashionable, national states which engage in a war of interests can easily exploit national and cultural identities that are in competition with each other. Although ethnic groups can express themselves freely, in the easiest and most peaceful manner, very many of them readily enter into disputes and are incited to conflict. Personally, I am of the opinion that we must discuss the subject of our cultural identity in a flexible manner which does not give rise to clashes, be aware of the sensitivity of the topic, and not ignore reality.

What is your opinion about Turkey’s European outlook, as it emerges after the Helsinki summit?

The founders of the Republic of Turkey wanted to forge closer ties with Europe. Since then, unfortunately, the meaning of democracy in Turkey has not developed in parallel with Europe. We know the cause of this to be history and other political issues. Nevertheless, I interpret Europe’s acceptance of Turkey in historical and sociological terms. That is to say, that Turkey is too important for Europe to be discarded. The decision that was taken bears out what I say. Moreover, we shall see that the idea of being European will help society rethink its ideology and its exclusive dependence on the state. We can see that the state and its mechanisms are already coming into question. This was a dream of ours that was a long time coming.

If the European Union had not accepted Turkey, what would have happened?

We don’t even want to think about that, because Turkey has a lot of problems. One outcome of these problems is that they suffocate us. Who would that benefit – Europe, Greece, the Caucasus, the Middle East? Nobody, I think. In order to solve all these problems we need a broad horizon. This is what our links with the European Union have given us, to a certain extent. But it may not be enough. The Turkish people have a difficult life, with economic and social problems. For this reason, the time has come for Turkey to make some extremely important decisions and to embark on reforms in all sectors. Everyone accepts it, but it will not come about so easily. I think that the Turkish people are being tested by history. I believe that a successful outcome of this test will benefit everyone.

Newspaper : «International Herald Tribune», 25 April 2000

———————————————

—————————

——–

To νέο βιβλίο του Ομέρ που μεταφράστηκε και εκδόθηκε στα ελληνικά με τίτλο «Η κεμεντζέ του Νίκου« (δηλαδή «Η λύρα του Νίκου») θα παρουσιαστεί στην Αθήνα στις 15/9 στη Μεταμόρφωση Αττικής και στις 16/9 στο Polis Art Cafe…

To νέο βιβλίο του Ομέρ που μεταφράστηκε και εκδόθηκε στα ελληνικά με τίτλο «Η κεμεντζέ του Νίκου« (δηλαδή «Η λύρα του Νίκου») θα παρουσιαστεί στην Αθήνα στις 15/9 στη Μεταμόρφωση Αττικής και στις 16/9 στο Polis Art Cafe…

Η κεντρική παρουσίαση του βιβλίου θα γίνει την Παρασκευή 16 Σεπτεμβρίου, 2016, ώρα 19:30 στο ΠΟΛΙΣ Art Cafe ( Πεσμαζόγλου 5, Αθήνα).

Για το βιβλίο θα μιλήσουν οι:

-ΧΡΗΣΤΟΣ ΓΑΛΑΝΙΔΗΣ – Ο Πρόεδρος της Επιτροπής Ποντιακών Μελετών

-ΒΛΑΣΗΣ ΑΓΤΖΙΔΗΣ – Ιστορικός & Συγγραφέας

-ΑΛΕΚΟΣ ΠΑΠΑΔΟΠΟΥΛΟΣ- Συγγραφέας & Εκδότης

-ΟΜΕΡ ΑΣΑΝ – συγγραφέας του βιβλίου

Η ηθοποιός ΑΝΝΑ ΤΖΑΝΑΚΑΚΗ θα διαβάσει αποσπάσματα από το βιβλίο.

Η ηθοποιός ΑΝΝΑ ΤΖΑΝΑΚΑΚΗ θα διαβάσει αποσπάσματα από το βιβλίο.

Την παρουσίαση θα συντονίσει η ΕΛΙΖΑΒΕΤ ΧΑΡΙΤΩΝΙΔΟΥ ΚΟΒΗ.

Ποντιακή λύρα (κεμεντζε) θα παίξει ο ΧΑΡΑΛΑΜΠΟΣ ΜΟΥΡΟΥΖΗΣ. Η τραγουδίστρια ΚΑΛΛΙΟΠΗ ΒΕΤΤΑ, με τον συνθέτη ΓΙΑΝΝΗ Κ. ΙΩΑΝΝΟΥ στο πιάνο, μαζί ο τραγουδοποιός ΔΗΜΗΤΡΗΣ ΕΡΑΤΕΙΝΟΣ και ο τραγουδιστής ΠΑΝΟΣ ΛΑΜΠΡΙΔΗΣ θα κλείσουν την εκδήλωση μαζί με ομορφύνουν με υπέροχα τραγούδια τους την παρουσίασή μας.

[…] απαγόρευσης του έργου του στην Τουρκία δείτε: Omer Asan: Greek-speaking writer from Turkey Περιμένoντας τον […]

[…] Omer Asan: Greek-speaking writer from Turkey […]

Ο Ταμέρ Τσιλιγκίρ (Tamer Çilingir) είναι Τούρκος πολίτης,καταγόμενος από την Ματσούκα (Maçka) του νομού Τραπεζούντος.Έχει βαθειά συνείδηση της Ποντιοσύνης του και διατηρεί σχέσεις με ποντιακούς κύκλους στην ελλάδα.Πρωτοστατεί δε στο ζήτημα της διεθνούς αναγνώρισης της Γενοκτονίας των Ελλήνων του Πόντου.Αν έχει ρωμαίικες καταβολές,αν αισθάνεται έλληνας,ας το αφήσουμε στον ίδιο να το εκδηλωσει Κυνηγημένος από το τούρκικο καθεστώς,ζει εδω και χρόνια στην Ελβετία.

Βρίσκεται σε επαφή με τούρκους ιστορικούς και ακτιβιστές και υπερασπίζεται τα δίκαια των ποντίων σε ανάλογα φόρουμ.Στην Ελλάδα είναι αρκετά γνωστός

και έχει συμμετάσχει σε ποντιακές Ημερίδες.Μέσω F|B ,συχνά επικοινωνούμε και ανταλλάσσουμε απόψεις.

Αυτός λοιπόν ο άνθρωπος, βαθειά σημαδεμένος από τον γενέθλιο τόπο του,πληγωμένος από τα όσα βιώνονται εκεί στην μεταβυζαντινή Τραπεζούντα και ιδιαίτερα τα τελευταία χρόνια,έγραψε ένα ποίημα στο πνεύμα του δικού μας ποιητή που τον πληγώνει η πατρίδα του όπου κι αν πάει.

Με συγκίνησε αυτό το ποιήμα,το μετέφρασα στα ελληνικά και σας το παρουσιάζω.

ΚΑΨΟΥ,ΕΞΑΦΑΝΙΣΟΥ,ΓΙΝΕ ΣΤΑΧΤΗ ΤΡΑΠΕΖΟΥΝΤΑ

Στα παιδιά που μοιράζουν φυλλάδια αποτρίχωσης,ορμάς με σφαίρες

Υποδέχεσαι τον τύρανο Ταγίπ φωνάζοντας «Οι μπάσταρδοι Αρμένιοι δεν μπορουν να μας τρομοκρατήσουν»

Κάψου,Εξαφανίσου,Στάχτη γίνε Τραπεζούντα

Εμείς με τις Αξίες του παρελθόντος μας,θα σε ξαναχτίσουμε

Ούτε μία,ούτε δύο,ούτε τρείς……….

Το 2005,αυτή που ώρμησε να λιντσάρει τίς μητέρες των κρατούμενων παιδιών

επειδή μοίραζαν ανακοινώσεις,δεν ήσουν εσύ?

Το 2006 εσύ δεν μαχαίρωσες τον Ανδρέα Σαντόρο,ιερέα στην καθολική εκκλησία της Παναγίας?

Και τον Χραν Ντίνκ,αυτή που τον μαχαίρωσε πισώπλατα πάλι εσύ ήσουν.

Δεν ντρέπεσαι Τραπεζούντα με την φτώχεια και τις ανομίες σου.

Εσύ,από τότε που έγινες από Τραπεζούντα Τράπζον,

άφησες τις ομορφιές του κόσμου και συντάχθηκες στο πλευρό των τυράνων

Εγειρες προς το πλευρό των εχθρών του Ανθρώπου

Εξ αιτίας αυτών των συμπεριφορών σου,φτάσαμε στο σημείο να μη λέμε ότι είμαστε Τραπεζούντιοι

Διότι μας ανάγκασες να σκύψουμε για ακόμη μία φορά το κεφάλι

Τι να πω? Ανάθεμάσε Τραπζον.

Και μην επιχειρήσεις να με παραμυθειάσεις με το επιχείρημα ότι δήθεν όλες αυτές τις άσχημες δουλειές

τις κάνουν κακοί άνθρωποι που βρίσκονται ανάμεσά μας

¨Ολα αυτά είναι έργα δικά σου,κατάδικά σου.

Από τότε που έχασες την ταυτότητά σου

Από τότε που πας χέρι χέρι με τους τυράνους

Από τότε που κατάστρεψες αυτούς που σε δημιούργησαν πριν 3000 χρόνια

Από τότε που ο καροποιός Νίκος,ο φούρναρης Κώστας,’εγιναν Αχμέτ,Μεχμέτ

Από τότε που στους καλούς ανθρώπους της πόλης σου,δ’ιδαξες την μαστοριά της σιωπής

εκτιμώντας ότι εξαφανίσθηκαν οι ομορφιές του παρελθόντος

Από τότε που η Τραπεζούντα μετατράπηκε σε Τραπζον

δεν είδαμε καμμία προκοπή.

Κ α ψ ο υ , Ε ξ α φ α ν ι σ ο υ, Σ τ ά χ τ η γ ί ν ε Τ ρ ά π ζ ο ν

Εμείς θα σε ξαναχτίσουμε από την αρχή

Με τις Αξίες 3000 ετών του παρελθόντος μας.

https://www.facebook.com/ theodoros.pavlidis.94 / δημοσιεύσεις / 1128504127184952